For the first time in years, there’s finally some optimism in the air about Germany’s economy.

After two consecutive years of contraction, the data points to a modest rebound. Forecasts are being upgraded, investor sentiment is rising, and the new government has opened the fiscal taps.

But the structural cracks that brought Europe’s largest economy to a near-standstill are far from repaired.

Is this the start of a recovery or just a temporary pause in a deeper stagnation? And most importantly, what is the path forward for Germany?

Has Germany’s economy already hit bottom?

Germany’s economy has barely grown since 2019. The cumulative real GDP increase over five years is just 0.1%. Over the same period, the eurozone grew by 4% and the United States by 12%.

The malaise has been persistent and broad-based, spanning exports, manufacturing, and investment.

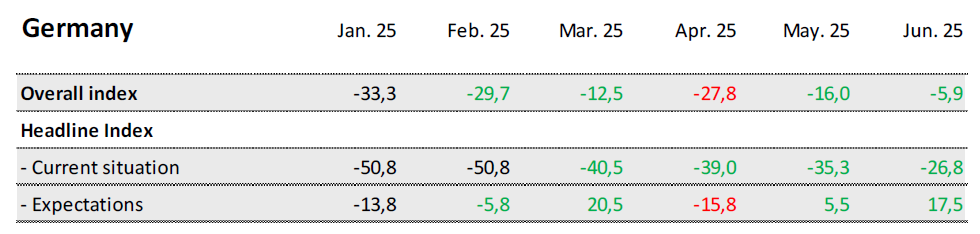

But recent news are more encouraging. According to Sentix’s June investor survey, Germany’s economic expectations have risen sharply to +17.5 points, the highest level since early 2022.

The current situation index is still negative at -26.8, but this is the fourth improvement in a row. The overall Sentix index, at -5.9, is now at a two-year high.

Since the index reflects investor sentiment and expectations, it often serves as an early indicator of where economic momentum may be building.

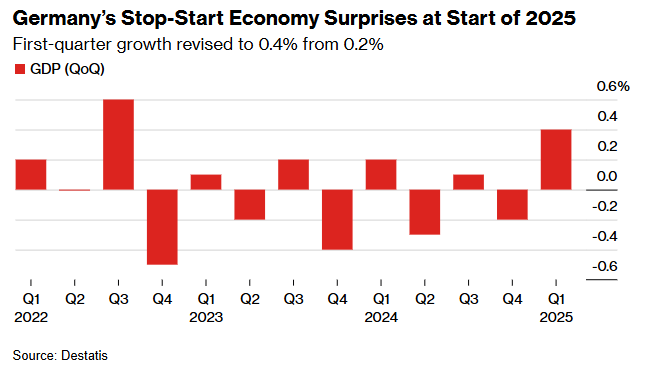

Furthermore, quarterly GDP growth of 0.4% in Q1 2025 helped turn the tone. That figure was double the initial estimate, driven largely by manufacturers and exporters rushing orders ahead of expected US tariffs on Europe.

While some view it as a front-loaded spike ahead of worsening trade conditions, the surprise was strong enough to prompt major economic institutes like the Kiel Institute and RWI, as well as Ifo, to revise their forecasts.

All three now see 2025 growth at 0.3%, up from near-zero or contraction territory just months ago.

For 2026, estimates range between 1.5% to 1.6%, which is 0.7% higher than previous estimates.

The reasons are primarily due to changes to Germany’s fiscal policy and renewed optimism following the elections.

Can an aging workforce power a modern economy?

Germany doesn’t lack jobs. It lacks workers.

According to the IMF, over the next decade, 20 million people are expected to retire, while only 12.5 million will enter the workforce. Labour shortages are already pushing up costs and slowing productivity.

Germany’s unit labour costs have risen faster than those of France or Spain. Even with energy prices cooling, labour has now become the primary cost pressure on industry.

The result is a slower economy that’s struggling to grow even with strong fiscal support.

So far, labour market reforms have lagged. Increasing full-time female participation could offer some relief, especially with nearly half of working women still in part-time roles.

Tying retirement age to life expectancy would help ease the demographic strain. But even these measures won’t close the gap on their own.

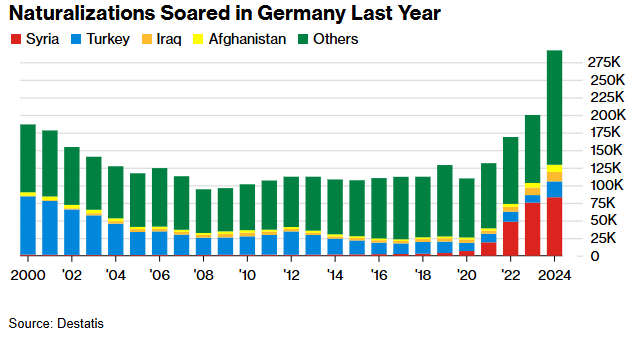

That’s why Germany is leaning towards immigration yet again. In fact, the country set a record last year, naturalizing more than 290,000 people, up nearly 50% from the previous year.

Many were Syrians and Russians, part of a wave enabled by looser citizenship laws introduced under the previous government. Residency requirements were shortened to five years, or even three for well-integrated individuals.

But that path is now being reversed. The new Merz government has already moved to scrap the fast-track process, citing political pressure to limit irregular migration.

The language barrier remains a big obstacle to Germany’s hopes of sourcing talented workers from the rest of Europe.

Without a consistent and forward-looking immigration policy, Germany will struggle to offset its aging workforce.

And without enough people in the workforce, even the best stimulus plans won’t push growth sustainably above one percent per year.

Is Germany still an industrial power?

The data suggests not. Since 2018, manufacturing output has been in steady decline. Exports have not recovered to pre-pandemic levels, even as global demand has returned.

Energy-intensive sectors are retreating, especially since 2022, when energy prices soared after Russia invaded Ukraine.

Electricity prices in Germany remain high, even higher than in the United States and most of Europe.

That limits the country’s appeal for modern industries like AI, where power-hungry data centers are a prerequisite.

More broadly, Germany remains locked into its legacy sectors: automotive, engineering, and chemicals. These industries still receive the bulk of private R&D investment.

But they are no longer engines of growth. New sectors like biotech and IT remain underdeveloped, not for lack of talent, but due to a lack of capital.

Venture capital in Germany has grown, but not fast enough. It reached just 0.09% of GDP in 2023. By comparison, US VC investment was over 0.5%.

German start-ups still rely heavily on bank loans, and those that scale often relocate to the US for access to deeper capital markets and IPO options.

Is there a path forward?

There is. But it requires more than stimulus.

Germany must expand its capital markets. That means pushing European-wide reforms to harmonize insolvency law and improve cross-border investment.

This also means better financial literacy at home. Retail savings are still concentrated in low-yield accounts.

A shift toward equity investment could help channel more funds into the real economy.

On the energy front, Germany can’t compete alone. A coordinated European energy market, a complete one with integrated electricity grids, would reduce system costs and attract new investment.

The same applies to services and regulation. Many non-tariff barriers still limit what is supposed to be a single EU market of nearly 500 million consumers.

This is the long game. The current government has taken bold first steps by lifting fiscal constraints.

But it must go further: rebuild infrastructure with speed, prioritize future industries, and make it easier for talent and capital to scale inside Europe.

If that happens, Germany could emerge from this stagnation not just intact, but stronger. If it doesn’t, then 2025 will be remembered not as the beginning of a recovery, but as a pause in a much longer decline.

The post Is there hope for Germany’s economy after all? appeared first on Invezz