Japan used to be considered the world’s most reliable creditor. But now, its economy is cracking from multiple fronts.

A collapsing bond market, inflationary pressure, external shocks from a potential trade war with the US, and an impossible debt burden are converging into what may be Japan’s most serious economic crisis in decades.

Slowly but surely, Japan’s economic situation is beginning to rattle global markets.

The shattering of a fiscal illusion

Maybe the signs were there for a while. Japan has run deficits larger than any other developed economy.

Its debt-to-GDP ratio has hovered above 260%. And yet, it paid almost nothing to borrow.

Investors didn’t mind. The Bank of Japan was always there.

The country’s massive pool of domestic savings was seen as a backstop. Markets assumed it could always fund itself.

That assumption is starting to crack.

In the first quarter of 2025, GDP shrank by 0.2%. Compared to a year earlier, the economy contracted by 0.7%.

Inflation rose to 3.5%, breaching the central bank’s 2% target for the first sustained period in more than a decade.

Real wages fell. Consumption stalled. Exports weakened, especially to the US which is Japan’s largest trading partner.

The economy isn’t just slowing. It’s showing signs of stress. And that stress is now showing up in the bond market.

Investors are walking away

Japan’s most recent 40-year government bond auction was the weakest in nearly a year.

The bid-to-cover ratio dropped to 2.21. Yields jumped to 3.135%, the highest level since the 1990s. Just days earlier, a 20-year auction recorded its worst demand since 2012.

These aren’t minor fluctuations. They mark a breakdown in confidence in the long end of Japan’s yield curve.

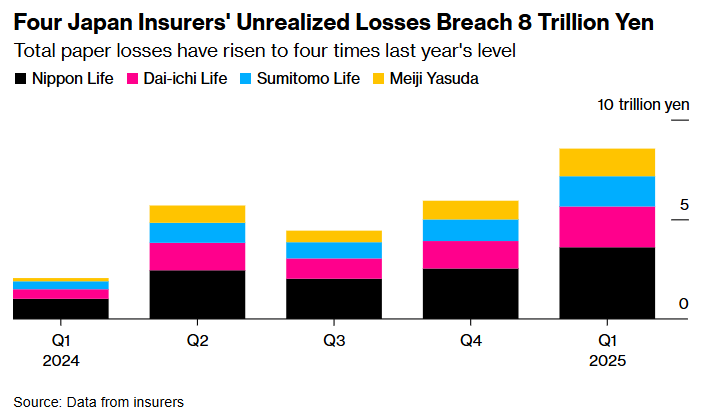

Major buyers, especially insurers and pensions, are reporting steep paper losses.

Japanese life insurers saw more than $60 billion in unrealized losses last quarter. Nippon Life alone took a $25 billion hit.

The Ministry of Finance has floated the idea of reducing issuance of ultra-long bonds to calm markets.

It worked for a day. But the underlying dynamic hasn’t changed. Investors are no longer showing up the way they used to.

Not the world’s top creditor anymore

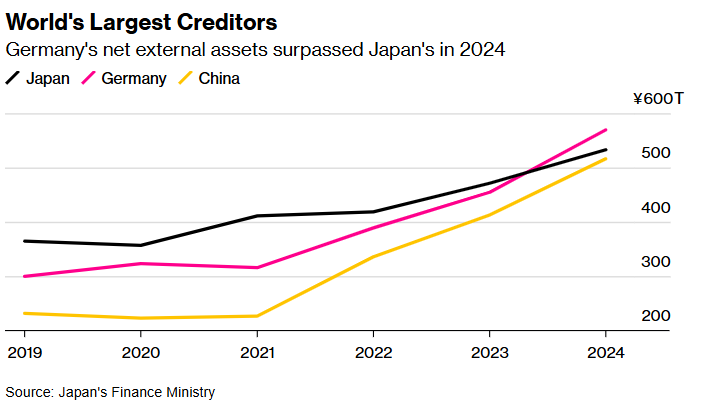

For the first time since 1991, Japan is no longer the world’s largest net creditor nation. That title now belongs to Germany.

At the end of 2024, Japan’s net external assets stood at a record high of ¥533 trillion, but still behind Germany’s ¥569.7 trillion.

Germany’s strong current account surplus, which reached €248.7 billion, and a 5% euro-yen currency move widened the gap.

Japan’s finance ministry tried to downplay the shift. Technically, Japan’s assets are still growing, driven by foreign direct investment, especially in the US and UK. But the mix of those assets matters.

More Japanese capital is now tied up in foreign businesses like banks, insurers, and retail, rather than in tradable securities. That means capital is stickier. If a crisis hits, it’s much harder to bring that money home.

The irony is that Japan’s growing global presence now makes its position more fragile. Investors know the liquidity of those foreign assets is limited. And they’re pricing that in.

Too much debt, not enough growth

The numbers are hard to ignore. Japan’s public debt now exceeds ¥1,400 trillion ($9 trillion).

That’s more than double the size of its economy.

For years, low interest rates and central bank bond buying kept the cost of that debt manageable. That safety net is fading.

The Bank of Japan has pulled back on bond purchases. Interest rates are no longer near zero.

Long-term yields are rising. Servicing the debt is getting more expensive at the worst possible time.

And Japan can’t grow its way out of it. The population is shrinking.

The workforce is aging. Potential growth is capped at about 1%. Q1’s contraction may not be a one-off.

The illusion that Japan’s debt didn’t matter worked as long as interest rates stayed low. That illusion is breaking down.

Trade pressure is making things worse

While Japan is dealing with internal weaknesses, external pressure is escalating.

In April, President Trump imposed a 25% tariff on Japanese automobiles and a 10% tariff on other imports.

He’s also threatening a 24% reciprocal tariff if a deal isn’t reached by July.

This is not just about trade friction. The US is Japan’s most important export market. The auto sector is central to Japan’s economy.

Toyota expects a $1.3 billion hit to earnings in just two months. Nissan is already preparing to shut down domestic production and shift output to the US.

These tariffs aren’t just hitting corporate profits. They’re weighing on investor expectations, complicating monetary policy, and narrowing the government’s room to respond.

Policy is trapped, and politics is fraying

The government faces elections in July. Prime Minister Shigeru Ishiba is resisting calls to cut the consumption tax.

Others in his party say not cutting taxes could cost them power. Protesters have started gathering outside the Finance Ministry, something almost unheard of in Japan.

For years, Japan managed political pressure with public spending.

Subsidies, transfers, and infrastructure projects helped avoid the kind of populist backlash seen in other rich countries.

That tool is becoming harder to use.

Rising borrowing costs are forcing a choice. Cut back and risk social unrest. Or spend more and risk further bond market pressure. There’s no easy middle path.

The yen can’t move either

In many crises, a weaker currency helps. It boosts exports, softens debt burdens, and supports growth. But Japan can’t afford that right now.

The yen is already near multi-decade lows. A further drop would worsen inflation.

More importantly, it would widen Japan’s current account surplus, something Trump has already criticized.

Any move by the Bank of Japan to ease further could provoke more US tariffs.

That puts monetary policy in a bind. Raising rates risks choking growth. Easing risks escalating trade tensions and inflation. For now, the central bank is doing neither.

A message for the rest of the world

Japan’s bond market used to be the safest in the world. It’s been stable through crises, recessions, and deflation.

But 2025 is different. Inflation is back. Growth is weak. Debt is expensive. And buyers are no longer showing up.

This matters far beyond Tokyo. Japan is the largest foreign holder of US Treasuries. If capital begins to flow home in search of higher domestic yields, the effects will show up in global bond markets.

Treasury yields are already moving.

What’s happening in Japan isn’t just a domestic story. It’s a warning that the era of costless debt is ending, and that even the safest borrowers are not immune.

The post Japan economy is facing a breakdown investors didn’t see coming appeared first on Invezz