Something unusual is happening in global currency markets, and most people aren’t paying attention.

This week, the Taiwan dollar surged more than 5% in a single day, recording its biggest jump since 1988.

At the same time, Asian banks, exporters, and sovereign funds are increasingly trying to bypass the US dollar in their transactions.

It’s not a full-blown crisis, yet, but the message is clear: confidence in the US dollar is slipping, and capital is moving.

What used to be a slow drift is now turning into something larger. A big paradigm shift is underway in Asia, and the US may not be ready for it.

Is the US dollar still the world’s anchor?

For decades, the dollar has been the backbone of the global financial system.

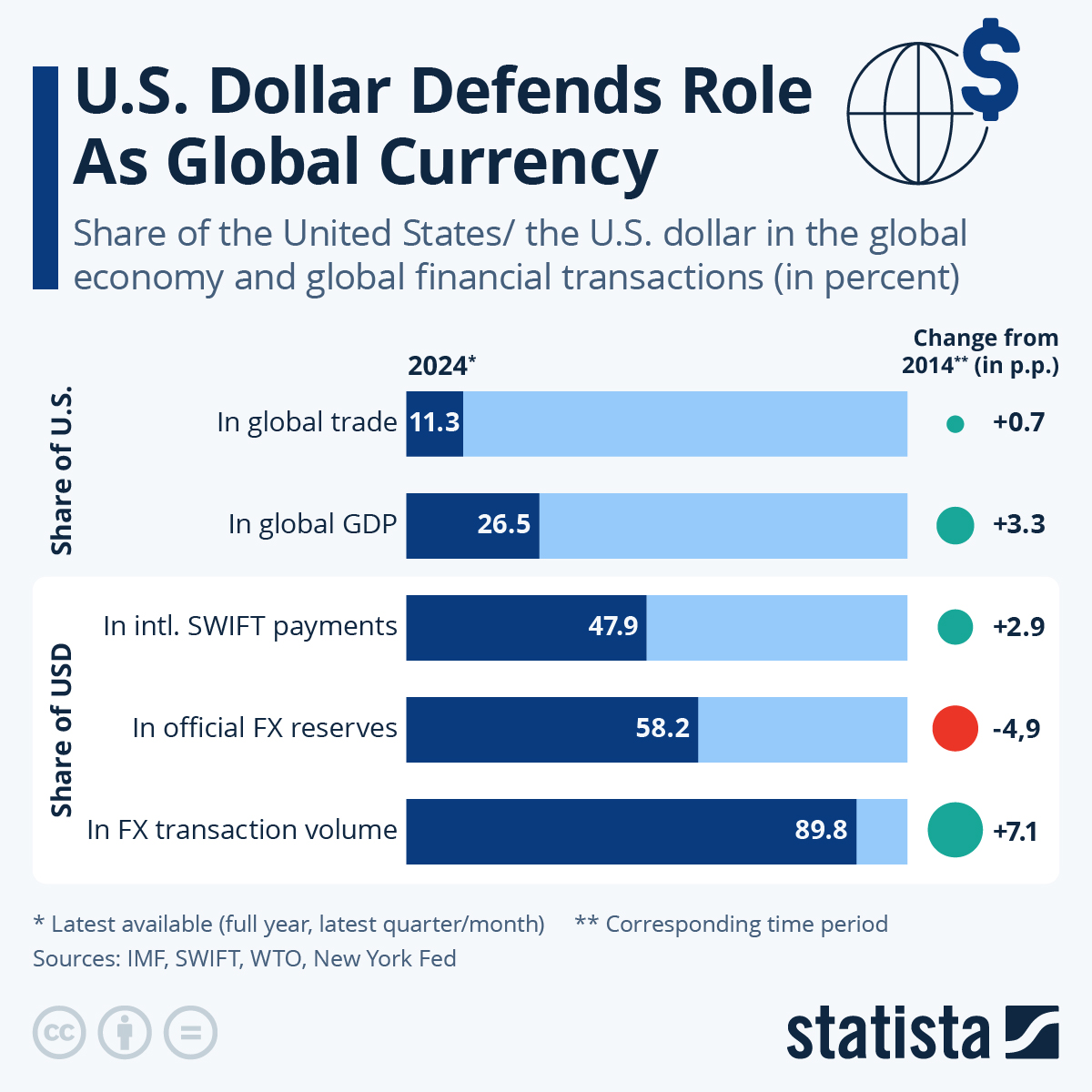

According to a seminal 2021 paper, It is used in 88% of all currency trades.

Roughly half of all global trade is invoiced in dollars, and the greenback still accounts for more than half of global foreign exchange reserves.

But that grip is beginning to loosen. So far this year, the dollar index (DXY) is down by almost 8%, the sharpest year-to-date decline in its 20-year history.

At the same time, most Asian currencies strengthened sharply against the dollar.

Taiwan’s dollar was the standout, gaining 5% in one day after exporters rushed to sell their dollar holdings.

The offshore yuan hit a six-month high.

The Hong Kong dollar tested the strong end of its trading band, triggering a $6 billion intervention by its de facto central bank.

None of these moves were isolated.

They are part of a wider trend. Asian institutions, from central banks to insurance funds, are repatriating dollar-denominated assets and hedging their exposure.

Demand for dollar hedges has surged. Some firms are even placing restrictions on trading platforms to cope with the flood of conversion requests.

This week, Stephen Jen, a former IMF economist known for his “dollar smile” theory, estimated that Asian exporters and institutional investors hold up to $2.5 trillion in unhedged dollar positions.

If even a fraction of that moves, it could accelerate the pressure on the dollar and fundamentally alter how global finance works.

What’s driving these currency fluctuations?

The immediate trigger is none other than President Trump’s economic agenda.

Since returning to office, he has ramped up tariff threats and pushed trade talks into a stalemate.

US tariffs on Chinese goods currently stand at 145%, with little indication of a near-term rollback.

In return, Beijing has made it clear it expects the US to cancel what it calls “unilateral tariffs” as a condition for meaningful talks.

Both sides are posturing, but the pressure is real.

The US economy shrank in the first quarter, marking the first contraction since 2022.

China’s manufacturing index also slipped into contraction.

Both countries are dealing with slower demand, weaker exports, and rising capital tensions.

But the difference is that while the US still leans on the dollar’s global status, Asia is quietly adjusting its strategy.

Exporters in Taiwan, China, and Southeast Asia are no longer holding onto dollars.

They’re exchanging them faster for local currencies, betting that the dollar will weaken further.

In some cases, they’re taking the hit on higher hedging costs just to get out.

That’s not a speculative move; it’s risk management.

And it’s being matched by action at the institutional level.

Banks across Asia are seeing increased demand for currency derivatives that bypass the dollar entirely.

That includes euro-yuan trades, rupiah-yuan swaps, and direct hedging in the Hong Kong dollar.

A foreign bank in Indonesia is even setting up a dedicated yuan trading desk to meet local demand, according to Bloomberg.

Is this the beginning of de-dollarization?

Technically, yes. But not in the dramatic sense people often imagine.

The dollar is not being replaced overnight, and there is no credible alternative with the same depth, liquidity, or reach.

The euro’s share in global transactions has actually declined over the past two years.

And while the yuan is gaining ground, it still only accounts for about 4% of global payments, according to SWIFT data from March.

However, the trend is unmistakable. China’s Cross-Border Interbank Payment System (CIPS), its alternative to SWIFT, cleared $24 trillion in transactions last year, up 40% from 2023.

The yuan is now being used in record volumes for China’s cross-border trades, especially with Southeast Asia and the Gulf.

Exports to those regions have grown by over 80% in the last five years, compared to much slower growth with the US and EU.

This is where the dollar’s dominance starts to erode, not from a sudden collapse, but through slow, deliberate changes in how companies and countries transact.

If the dollar becomes just one of many options, rather than the default, its role will shrink.

The cost of hedging the dollar has also increased over the past year, especially around key political events like the US election and trade policy announcements.

Traders are now pricing in more risk for holding dollars, not less.

What are the bigger risks?

The deeper risk isn’t volatility, but credibility.

The dollar’s global status rests not just on economics, but on trust. That trust is weakening.

When the US froze Russia’s dollar reserves after the Ukraine invasion, it sent a signal that access to the dollar system could be politically conditional.

Since then, more countries have started building alternatives.

President Trump’s approach has amplified that perception.

His repeated attacks on the Federal Reserve, his unpredictable tariff policy, and his open complaints about the dollar’s strength have all made investors uneasy.

At the same time, the US is running persistent deficits, and its room for monetary easing is more limited than before.

Foreign demand for US Treasuries has already declined.

At recent auctions, the share of buyers categorized as “indirect” (which includes foreign central banks) has fallen.

If that trend continues, financing US debt could become more expensive, especially if interest rates fall and investors start looking elsewhere for return and stability.

This isn’t just about currency markets. It’s about the architecture of global capital flows.

If fewer countries are willing to hold the dollar as a reserve asset, or use it as a trade intermediary, that changes the playing field.

At the end of the day, no one expects the dollar to disappear.

But in the world of global finance, it doesn’t need to vanish to lose power.

All it takes is for enough players to choose something else. And countries are beginning to look at their options.

The post Why Asia is quietly turning its back on US dollar appeared first on Invezz